|

|

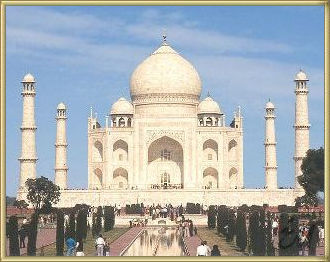

Copyright 2000 Noreen Majeed The Taj MahalThe most beautiful building in the world. In 1631 the emperor Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal in memory of his wife Mumtaz, who died in childbirth. The white marble mausoleum at Agra has become the monument of a man's love for a woman. Shah Jahan came to power in 1622 when he seized the throne from his father, while murdering his brothers to ensure his claim to rule. He was known as an extravagant and cruel leader. But he redeemed himself by his generosity to his friends and the poor, by his passion in adorning India with some of its most beautiful architecture, and by his devotion to his wife Mumtaz Mahal - "Ornament of the Palace." He had married her when he was 21, when he already had two children by an earlier consort. Mumtaz gave her husband 14 children in eighteen years, and died at the age of 39 during the birth of the final child. Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal as a monument to her memory and her fertility, but then relapsed into a life of scandalous behavior. This tomb was only one of hundreds of beautiful buildings that Shah Jahan erected, mostly at Agra and in the new Dehli that came into being under his planning. Many architects have rated it as the most perfect of all buildings standing on earth. Three artists designed it: a Persian, an Italian, and a Frenchman. But the design is completely Mohammedan. Even the skilled artisans who built it were brought in from Baghdad, Constantinople, and other centers of the Muslim faith. For 22 years more than 20,000 workmen were forced to build the Taj. The Maharaja of Jaipur sent the marble as a gift to Shah Jahan. The building and its surroundings cost more than $200,000,000 in todays currency. Passing through a high wall, one comes suddently upon the Taj - raised upon a marble platform, and framed on either side by handsome mosques and stately minarets. In the foreground spacious gardens enclose a pool in whose waters the inverted palace becomes a quivering dream. Every portion of the structure is of white marble, precious metals, or costly stones. The building is a complex figure of twelve sides, four of which are portals. A slender minaret rises at each corner, and the roof is a massive spired dome. The main entrance, once guarded with solid silver gates, is a maze of marble embroidery; inlaid in the wall in jeweled script are qotations from the Koran, one of which invites the "pure in heart" to enter "the gardens of Paradise." Shah Jahan had begun his reign by killing his brothers; but he had neglected to kill his sons, one of whom was destined to overthrow him. In 1657 his son Aurangzeb led an insurrection from the Deccan. Aurangzeb defeated all the forces sent against him, captured his father, and imprisoned him in the Fort of Agra. For 9 bitter years the deposed emperor lingered there, never visited by his son, attended only by his faithful daughter Jahanara, and spending his days looking from the Jasmine Tower of his prison across the Jumna to where his once-beloved Mumtaz lay in her jeweled tomb. The new emperor Aurangzeb was a more pious Muslim than his father Shah Jahan had been. He memorized the entire Koran, spent days in fasts, and campaigned against infidelity. He cared little for luxuries, but, paradoxically, gave the world one of its most perfect works of art: a marble screen inside the Taj Mahal. Native and European thieves robbed the tomb of its abundant jewels, and of the gold railing, encrusted with precious stones, that once enclosed the sarcophagi of Shah Jahan and his Queen. Aurangzeb replaced the railing with an octagonal screen of almost transparent marble, carved into a miracle of alabaster lace. Few products of human art have ever surpassed the beauty of this screen. From afar the Taj Mahal, with its delicate details, is not imposing. Only a nearer view reveals that its perfection has no proportion to its size. When in our hurried times, we see enormous structures of a hundred stories raised in a year, and then consider how 20,000 men worked for 22 years on this little tomb, hardly a hundred feet high, we begin to sense the difference between industry and art. And perhaps more importantly, we sense the ultimate lesson it offers: beauty and that which lasts, is based on love. Adapted from: Our Oriental Heritage, Will Durant, Simon and Schuster, 1954 More photos:

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||